First of all, I have to say that as well as encouraging me to not be so prudish/picky about what I read, the Banging Book Club (led by three of the most interesting and intelligent YouTubers) provides a great starting point for discussions whether it was an off-the-cuff comment in their non-spoiler videos (I found Lucy's description of the book as 'a cautionary tale' interesting and worthy of more discussion) to the in-depth discussions on the podcast. In fact, I had started writing this when I listened to the podcast and I now regret not waiting - for now, it produced some Incidental Thoughts (see bottom of this post) but future posts on books from Banging Book Club will be written post-podcast.

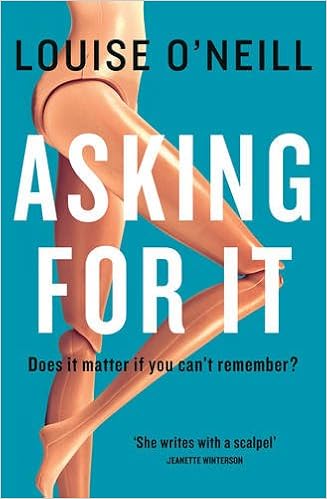

So my initial thoughts were coloured by my slow-reading - having read the first part set 'Last year' I got a distinctly American Psycho vibe (I'll explain more below), which was then brutally stripped away when I reached the second section and the stark realism of 'This year'. As always, it's taken me a while to get to a synopsis of the book, but frankly I think the book itself tells you everything you need to know from its cover

|

| I would like it if this happened to someone else. I would like it if someone else was ruined too. I wouldn't be alone. |

Maybe she [her mother] wishes that I had died too. Would that have been an easier grief than this, looking at me every day and knowing that this was only a shell, that Emmie, the real Emmie, was never coming back and that there was a new Emma that she had to learn to love all over again?While I said there's a shift into realism - and there is, in that we dive deeper into Emma's psyche rather than the fleeting hints and clues buried under her desire to be popular - it's only that the flashy superficiality of Emma's life is replaced by a 'realist' aesthetic. It is more strip-backed but is no more honest as there are no easy or honest conversations - whereas before there was a routine as part of a game everyone was in on, here it is more stilted as Emma claims, "I don't know what to say. Tell me my lines please" and that her mother 'doesn't like it when I [...] go off script." This need to find the right way to talk about rape and the stigma that affects how we talk about it is something that concerns me particularly and I think is interestingly addressed in the novel. Rather than lecture about the morality of how we should treat rape victims (and how damaging that label can be regardless of good intentions), it remains observational in presenting its reality as Emma evidently struggles to cope with how she is treated, whether it is through supportive hashtags or judgemental condemnations - it's all unhelpful and raises the question: "When did we all become fluent in this language that none of us wanted to learn?" Even writing this review, I'm worried about writing the wrong thing or, even worse, falling into the cliched phrases that surround this topic and so are becoming increasingly useless as they become more generalised. Is there a right language for discussing this? I can't answer this, and neither does O'Neill, instead she goes for honesty - she, and Emma unsurprisingly, show an awareness of how her victimisation is treated and represented, and to me, that is the novel's greatest strength: addressing the issue head-on rather than trying to judge as pretty much every single character does.

Right from its front cover, the novel shows an engagement with what seems to be the ongoing (and seemingly never-ending) social issue of rape, consent and why its all got so complicated. O'Neill uses the phrases that sound so cliche and stereotypical yet all too familiar in order to attack them (and the attitudes they represent) with a scalpel (to borrow Jeanette Winterson's description of O'Neill's style) that it is also necessary to at least address them in any exploration of this subject matter. What is particularly impressive is how Emma remains a three-dimensional character with O'Neill just avoiding her becoming a passive victim in her own story, even as she explains how

my brain is crammed up with that word and those photos and those comments (her tits are tiny, aren't they?) and I don't have any room for anything else.Her life has been consumed by this event so yes she is passive, but she is by no means willing to be a part of this narrative even as there are no signs of escape.

Saying all that, to develop the above description, while there is a fierce yet controlled satirical edge to O'Neill's writing which warrants Winterson's cover-friendly quote, I don't think it is as delicate as the phrase suggests - this is a pointed attack and there are plenty of scars made by O'Neill. She does not hide her her horrified viewpoint on the situation Emma finds herself in which I'm in no position to deny or praise in terms of accuracy. What that means though is while I am on O'Neill's side, I feel some subtlety was lost and the novel felt less realistic and more polemic. Although perhaps my unease really comes from the fact that the novel sits between those two positions - I never felt lectured but then I couldn't quite believe in the reality of the novel either. (NB While Emma's situation is not exclusive to women, I doubt being a man helps with my identification problem which I notice few female readers claim to see)

And perhaps that's the point. We can't understand this situation because it is so remote from our lives even though it isn't as remote as we think - indeed our careless attitude is precisely the problem. Seeing it from Emma's perspective means we naturally sympathise with her struggles while never being sure how malicious the intent is by those who cause her suffering. No doubt this is an uncomfortable read, but like American Psycho, it is made somewhat palatable by its satire. But this is not feel-good satire - to walk away from this book feeling educated and smug at seeing a new perspective ignores what the book tries to do. This is harsh satire, stuff that is painful to laugh at but the urge is there regardless. This is satire with bite and proof that satire doesn't have to be uproariously funny as long as it takes a side swipe at the world it is depicting.

One last repetition to end this review on: A provocative take on an uncomfortable subject matter that reminds us we should never be comfortable discussing this subject, which is why we must.

Incidental Thoughts from the podcast

- It struck me that there is a famously unlikeable literary character called Emma - Jane Austen's Emma. Makes me wonder if O'Neill's Emma could be read as a modernised version of Austen's Emma who is unlikeable but not unsympathetic, except she is not given a happy ending.

- I found Hannah's question about whether someone could read this and think she was asking for it fascinating - I think it could be very easily read as a one-dimensional reactionary polemic, either in glorifying victim shaming with a 'she had it coming' attitude or glorifying victim shaming with a 'pity the poor rape victim because she's a rape victim, not because she's a human being' attitude. (I realise I've probably expressed myself poorly there, but hopefully the two extremes are clear)

- I can't help wondering if the novel is being manipulative - I mean all art ism but developing from that above point, does the subject matter dominate the novel too much? Is it too much of a social issues novel? Is that even a criticism? As I say, it is certainly provocative so the fact it raises so many questions, I can only consider a good thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment